Remembering 'Uncle George' - the Churchover farm labourer with an extraordinary talent

There are undoubtedly many people living in and around the Rugby area who will feel a sense of sadness regarding the loss of so much green space in recent years.

The town has expanded greatly over the last few decades and this process seems set to continue.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBeing a son of Churchover, the most dramatic changes for me have been brought about by the Gateway expansion up to the M6, because it was in those former green fields that I spent much of my boyhood.

All that remains now is a spinney, a lonely and forsaken island of Nature set in a sea of warehouses and other buildings.

Whenever I gaze at this mass of bricks and concrete, my thoughts once again turn to memories of the rural idyll that was this corner of 1950s rural north-east Warwickshire.

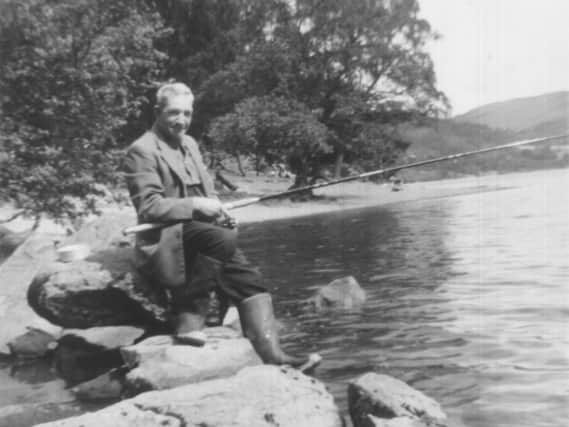

In particular, I reflect on those happy days when I would go shepherding on spring and summer evenings with ‘Uncle’ George, a farm labourer who lived over the road from me in School Street.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis was back in the days when a friend of the family might be called ‘Uncle’ or ‘Auntie’ and so it was permissible to dispense with the more usual formalities of that lost, more deferential era.

Much water has flowed under the bridge of the nearby River Swift since then, but I can still somehow feel the turf below my feet, see the barn owls quartering the hedgerows, hear the rooks cawing in the spinney, and watch as the lapwings call ‘peewit’ as they take off from their nests in the grass tussocks.

Tragically, they are all now gone, sacrificed on the much-worshipped altar of that deity some might call progress.

George Hirons worked at Jack Mace’s Farm and was never off duty.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThat’s why he would head off across the fields in the lighter evenings in order to count the sheep and cattle, check there were no holes in the hedges, and make sure the fences were not damaged.

To be in George’s company was an education all in itself. There was nothing he didn’t know about local wildlife and country lore.

He could even sneak up on a hare and catch it by its ears. Yes, true.

But there was one other gift that made George special. He was a ‘dowser’ or ‘diviner’, an art which is still shrouded in mystery, and one that still baffles scientists.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdI was brought up in Woodbine Cottage, an ancient dwelling dating from the 16th century. It is reputed to be haunted, although I never once sensed or encountered any spirits when I lived there.

Anyway, my parents were aware of a well that lay concealed somewhere in the garden, in those days a verdant expanse covering around a third of an acre of land. The trouble was that they had no idea where to start their search.

And this is where George came in. There must have been a conversation at some stage, and it was then that George revealed his special talent. All he would need was a forked hazel stick and the rest would be taken care of by… well, no one really knows what else.

George discovered the well almost immediately. Starting in the front garden, he took a westerly direction and there, underneath the turf on the front lawn, about a foot down, was that well.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdGeorge had been holding the hazel stick by the forked end, and when it abruptly almost did a complete somersault of its own accord, he knew he’d found what he was looking for.

There are various theories about how this works, why hazel wood is preferred by some dowsers – perhaps it has special conducting qualities – but from what I can make out, no one has ever come up with a definitive answer.

Another skill George demonstrated was if a ewe had lost its lamb. With a bit of luck, if there was also a lamb that had lost its mother, George would take the skin from the dead animal and wrap it round the orphaned one. The mother of the dead lamb would then accept the waif and stray as its own.

Despite a legendary cigarettes habit, George died at the ripe old age of 92. He is buried in the graveyard at Holy Trinity, Churchover, and I never fail to pay him a visit whenever I’m in the Rugby area.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnd whenever I do, my thoughts will always turn back to those long lost summer evenings when I would set off with him across those verdant fields that once echoed to the sound of the birds, but now sadly reverberate to the machines of Mankind.

John Phillpott worked on the Rugby Advertiser from 1965 to 1969. His book Beef Cubes and Burdock is a memoir of his country childhood and available from bookshops and Amazon.